The Comprehensive Checklist of Assets People Forget in Their Wills

Why Forgotten Assets Matter in Senior Estate Planning

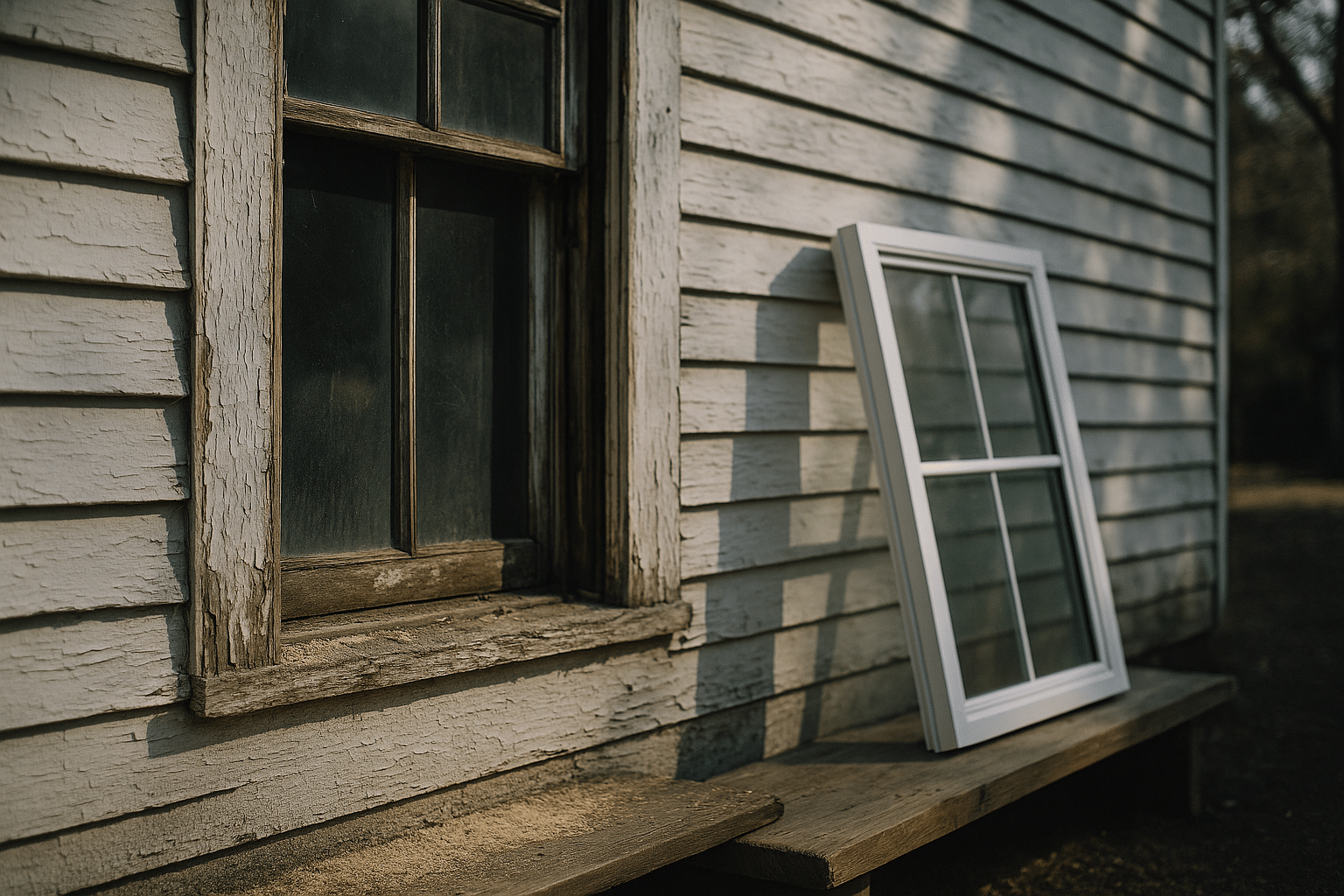

Seniors often have decades of financial footprints: jobs, homes, hobbies, savings plans, and online accounts that evolved as life changed. The result is a patchwork of assets—and a few strays hiding in the margins. When these assets don’t make it into a will or estate plan, families face delays, avoidable fees, and hard choices during an already stressful time. Probate can take longer to close, taxes can rise inadvertently, and sentimental items may cause disagreements if intent isn’t crystal clear. Think of forgotten assets as the squeaky floorboards in a well-built house: small gaps that become loud problems when you walk over them.

The impact is larger for seniors because the asset list is simply longer. There may be old employer plans, dormant accounts, a storage unit from a downsizing, or a small parcel of land inherited decades ago. Over time, even modest oversights can snowball into real money; states collectively hold more than seventy billion dollars in unclaimed property, a sign that assets commonly slip through the cracks. Add the growth of digital life—logins, credits, and subscriptions—and it’s no wonder families miss key pieces. Good news: a methodical checklist closes these gaps and helps turn a scattered record into an orderly legacy.

Here’s the outline we’ll follow before diving into details and examples:

– Tangible property and sentimental items that routinely get overlooked

– The digital footprint: emails, cloud files, domains, and cryptocurrencies

– Financial accounts, income streams, and benefits that bypass the will

– Real property, deeds, and special rights that hide in plain sight

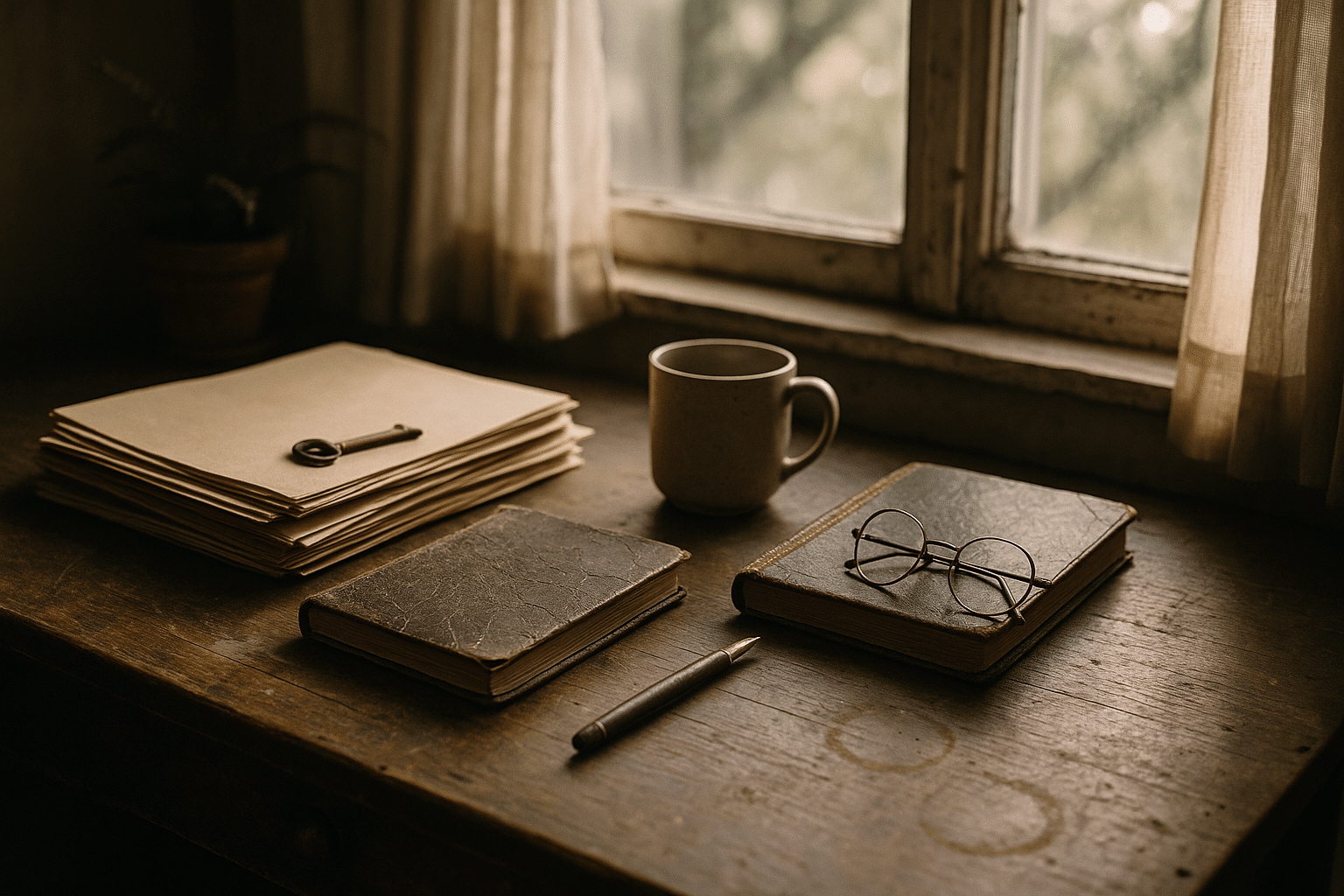

– A practical, senior-focused process to inventory, document, and update

As you read, compare how different ownership structures interact with a will. Some assets pass via beneficiary designations or transfer-on-death tools and never touch probate; others depend entirely on the will’s wording. We’ll highlight those differences so your plan matches how the law actually moves property. The goal is not perfection; it’s clarity, so loved ones can carry out your wishes without guesswork or gridlock.

Tangible Property and Sentimental Items People Forget

The simplest assets are often the most invisible. Everyday belongings—tools, jewelry, heirlooms, musical instruments, hobby gear, antiques, and collections—might not be on a brokerage statement, but they can be emotionally priceless and financially meaningful. Seniors frequently accumulate curated items over a lifetime: a carefully assembled stamp collection, a cabinet of fine china, or a workshop filled with specialized equipment. Without specific guidance, these items drift into the general estate and may be sold off or divided in ways that don’t reflect your intent. That’s when friction arises: siblings may remember different promises, or executors may not know which piece was “supposed to go to whom.”

Start with a room-by-room inventory, taking photos and listing any item you would regret seeing mishandled. In many families, a simple letter of instruction paired with the will is enough to reduce tension. Use clear descriptions so there’s no confusion between “grandmother’s cameo brooch with a small crack” and “the round brooch with a floral pattern.” Appraisals matter more than many think; collectibles’ values can vary widely based on condition, provenance, and recent auction data. If the asset is meaningful or potentially valuable, consider a credible appraisal and keep a copy with your estate papers.

These are common tangible oversights:

– Storage-unit contents, especially after a downsizing

– Safe-deposit box items that no one else knows about

– Vehicles, recreational equipment, and trailers with unclear titles

– Tools and machinery that could be worth thousands if sold properly

– Memorabilia, art, and antique furniture where value is not obvious

Compare two approaches for personal property: specific bequests versus a residuary catch-all. Specific bequests let you name individual items for particular recipients, preserving stories and intent. A residuary clause sweeps everything else into a pool for sale or distribution, which is efficient but less personal. Many seniors blend both: they earmark heirlooms and high-value items, then direct the rest to be divided or liquidated. Add a practical system, such as color-coded stickers or a documented priority list, to avoid disputes. Finally, remember that some items may require special handling (for example, restricted antiques or regulated equipment); note any legal steps in your instructions so your executor is not surprised midstream.

Your Digital Footprint: Accounts, Access, and Hidden Value

In the digital age, a large portion of estate value is stored behind passwords. Email accounts hold receipts, invoices, contracts, and a map to other services. Cloud storage can include family photos, scanned records, and creative work; social platforms may have memorialization options or downloadable archives; and storefront or marketplace accounts can contain sales histories or balances. Subscription credits, digital wallets, domain names, blogs, and monetized channels may represent income potential or at least intellectual property worth preserving.

The governing framework for accessing digital assets is often state law that allows fiduciaries limited access under defined conditions. If your state has adopted modern digital-access statutes, your executor or designated agent may be able to obtain necessary data with the right documents. Even so, you should not rely on court orders alone. A simple list of key accounts, the location of a password manager, and directions for two-factor authentication devices can be the difference between a smooth transition and a technological dead end. If you hold cryptocurrencies, document wallet locations, hardware devices, and recovery phrases with meticulous care; without them, the value can be permanently lost.

Consider these digital blind spots:

– Email accounts that prove ownership of other assets

– Photo libraries that family members want to preserve

– Domain names and personal websites with renewal dates and resale value

– Store credit balances, gift card codes, and loyalty points with transfer options

– Online business dashboards, ad revenue accounts, and affiliate payouts

Compare a traditional will to a digital asset authorization. A will distributes property but often does not grant service-specific permissions. Many platforms let you set a legacy contact or name a person who can download data or manage a memorial page; use those tools in tandem with your estate plan. Keep instructions separate from the will so you can update them easily as logins change. Provide practical breadcrumbs: where the master list is stored, how to access encrypted files, and who knows the location of backup keys. Treat your digital life like a library—catalog the shelves, label the sections, and leave a helpful map for the next librarian.

Financial Accounts, Income Streams, and Overlooked Benefits

Many valuable assets never pass through a will at all, which is why seniors should double-check beneficiary designations and payable-on-death instructions. Bank accounts, retirement accounts, annuities, and life insurance typically transfer by contract, so the beneficiary form controls the outcome. That’s helpful for speed, but it also means the will cannot fix an outdated designation. Old employer plans, closed credit union accounts, or forgotten savings bonds are frequent culprits; over a lifetime, it’s easy to accumulate a handful of accounts that no one remembers. States report holding tens of billions in unclaimed property, much of it from dormant financial accounts. A periodic sweep for lost assets can unlock meaningful sums and close lingering gaps.

These categories deserve special attention:

– Retirement plans from previous employers (confirm rollovers and beneficiaries)

– Health savings accounts and medical reimbursements that are still pending

– Small annuities or pensions with survivorship options you may have forgotten

– Dividends and dividend reinvestment plans that keep creating new shares

– Royalties, licensing income, and residuals from creative or technical work

Compare will-based distribution to contractual transfers. A will can direct the residue of your estate, but a beneficiary designation overrides it for that specific account. Coordinating both prevents unintended inequities. For example, if one child is named on a retirement account and the will divides everything “equally,” the retirement account may skew the total distribution. Map the whole picture, then adjust designations or bequests to match your intent. Also consider tax differences: retirement accounts may have distinct income tax implications for heirs, while life insurance proceeds typically do not count as taxable income for the beneficiary. A clear inventory, paired with sound advice, keeps taxes predictable and distributions aligned with your goals.

Don’t forget government or employer-related benefits. Survivor pensions, accrued vacation payouts, and last paychecks may be owed. Utility deposits, security deposits, and prepaid service credits can be reclaimed with the right documentation. If you have business interests, identify buy-sell agreements, receivables, and any promissory notes owed to you. Keep statements, policy numbers, and contact details in one place, with a simple flowchart that shows who to call first and what to request. A little administrative foresight turns a maze into a well-lit hallway.

Real Property, Deeds, Special Rights — and a Senior-Focused Conclusion

Real estate presents unique opportunities and traps. Title controls outcome, and the details matter. Joint tenancy with right of survivorship will usually bypass probate, while tenants in common will flow through the will. Some states allow transfer-on-death deeds that move property to a named beneficiary upon death; that’s efficient but must be set up correctly and updated when life changes. Condominiums and cooperatives may have approval processes or bylaws that affect transfers. Timeshares, cemetery plots, mineral or water rights, and small fractional interests in distant parcels can be hard to locate yet meaningful to heirs. If there is a mortgage, tax lien, or homeowner association balance, those obligations follow the property and need to be documented in the plan.

Common real property blind spots include:

– A vacation lot or hunting acreage retained from decades ago

– Mineral or royalty interests recorded in a county two states away

– A family burial plot with unused spaces requiring assignment instructions

– A storage garage or boat slip with a separate contract and dues

– Refunds or tax abatements owed after a property sale or reassessment

Compare alternatives for keeping a home in the family: a will provision, a transfer-on-death deed, a life estate, or placing the home in a trust. Each tool has trade-offs for control, taxes, creditor exposure, and eligibility for public benefits. For seniors, clarity and simplicity are invaluable. If the goal is to allow a spouse or child to remain in the home, document who pays expenses, how repairs are authorized, and what happens if circumstances change. Keep copies of the deed, the most recent title report, and insurance declarations in the estate binder, with a short guide on where spare keys and utility shutoffs are located. Practical notes save time, money, and headaches in a crisis.

Conclusion for seniors and families: create a master inventory, then make it usable. Start with a one-hour “asset sprint” listing accounts, valuables, and logins; refine it over a week into a clean checklist. Store it in two safe places—one physical, one digital—and tell your executor where to find both. Update beneficiary designations, note special handling for digital assets, and earmark sentimental items with simple, plain-language instructions. Then schedule a yearly review, perhaps on a birthday or at tax time. The reward is peace of mind: your legacy delivered with accuracy, your stories preserved, and your loved ones spared the scavenger hunt.