Sterile Processing Technician Training Guide

Outline:

– Understanding the role and why it matters

– Training pathways and how to choose

– Core curriculum and competencies

– Hands-on skills, equipment, and workflow

– Exam preparation, career growth, and continuing education

The Role and Impact of Sterile Processing Technicians

Walk through any hospital and you’ll feel the pace pulse most in the operating suites. Behind those doors, sterile processing technicians are the steady hands that prepare instruments, maintain sterility, and support the rhythm of safe care. This is more than cleaning; it is a disciplined practice rooted in microbiology, quality assurance, and traceability. Studies estimate that surgical site infections affect a small but significant percentage of inpatient procedures, and every properly cleaned, packaged, and sterilized instrument tray helps reduce that risk. In short, when sterile processing is strong, patient safety is stronger.

Think of the role as a chain: decontamination, inspection, assembly, packaging, sterilization, storage, and distribution. Each link must hold. A single misassembled instrument can delay a procedure; a missed soil spot can shelter microbes; an incomplete log can obscure root cause analysis. The technician’s day blends attention to detail with time management. On a typical shift, you might prioritize urgent trays for trauma cases, coordinate with surgery for turnover needs, and verify cycle documentation for audits—all while maintaining a calm, methodical pace.

Daily responsibilities typically include:

– Receiving used instruments in a controlled decontamination area and applying standardized pre-cleaning steps.

– Inspecting for cleanliness and function under magnification and appropriate lighting.

– Assembling sets according to current count sheets and service line preferences.

– Selecting packaging materials that support sterilant penetration and aseptic presentation.

– Running sterilization cycles, recording parameters, and interpreting monitoring results.

– Rotating inventory and managing storage conditions to preserve sterility until point of use.

The impact extends beyond the operating room. Clinics, dental suites, and endoscopy units also depend on reliable reprocessing. Well-run departments support efficient case turnover, reduce instrument damage, and help contain costs. Data-driven improvements—such as tracking repair trends or analyzing cycle failures—can uncover upstream issues like water quality or workflow bottlenecks. For individuals who appreciate science, teamwork, and tangible results, the role delivers a purposeful career with visible contributions to patient care.

Training Pathways and How to Choose a Program

There is no single path into sterile processing, but most routes blend classroom learning with hands-on experience. Entry-level requirements generally include a secondary school diploma or equivalent, strong reading comprehension, and comfort with basic math and measurements. From there, candidates typically pursue one of three avenues: short-format certificate programs, comprehensive college-based courses, or structured on-the-job training under experienced mentors. Each pathway has trade-offs, and selecting the right one depends on budget, schedule, and local hiring preferences.

Certificate programs often run a few months and concentrate on foundational topics: microbiology basics, decontamination principles, instrumentation, packaging, sterilization methods, and quality monitoring. Many include a clinical externship ranging from dozens to a few hundred hours to satisfy common experience expectations. College-based options may extend to a semester or more, offering deeper coverage of anatomy, medical terminology, device design, and data systems, sometimes with embedded practicums. On-the-job routes can be attractive if a facility sponsors trainees while paying wages; success here hinges on structured checklists, documented competencies, and consistent coaching, which can vary by site.

When evaluating programs, consider:

– Curriculum scope: Does it cover the full workflow from decontamination through distribution and tracking?

– Practical hours: Are there sufficient, supervised clinical experiences with measurable skill sign-offs?

– Faculty and support: Do instructors have recent department experience and access to up-to-date equipment?

– Exam readiness: Are practice questions, scenario drills, and remediation built in?

– Job placement: Does the program maintain relationships with nearby facilities and offer resume or interview guidance?

Another dimension is alignment with widely recognized standards and certifications. While specific names and credentials differ across regions, reputable programs teach to established industry benchmarks—covering sterilization parameters, monitoring practices, and documentation essentials. Many employers prefer or require certification within a defined period after hire, so choosing a program that culminates in exam preparedness is pragmatic. Finally, weigh costs beyond tuition: textbooks, scrubs, immunizations, background checks, and transportation to clinical sites. A clear budget and timeline will help you select a pathway that supports steady progress rather than rushed compromises.

Core Curriculum: Science, Standards, and Competencies

Effective training starts with the science of contamination and control. Trainees study microbial types, biofilm behavior, and how soil—blood, tissue, lubricants—shields microorganisms from contact with detergents and sterilants. From that footing, the curriculum moves into instrument design and materials: the hinge of a rongeur, the lumen of a suction device, or the delicate edges of microsurgical tools each influence cleaning method, inspection techniques, and packaging choices. Human factors also matter: label clarity, lighting, and workflow sequencing can prevent errors before they begin.

Decontamination is the first critical gate. Learners practice safe transport, point-of-use pre-treatment, manual cleaning with brush selection, and mechanical cleaning via ultrasonic and washer-disinfector cycles. Water quality and detergent chemistry receive emphasis because mineral content, pH, and temperature affect soil removal and residue formation. Inspection then combines magnification, function tests, and verification of cleanliness indicators. Assembly and packaging focus on count accuracy, instrument protection, and device instructions for processing that dictate whether items can be wrapped, bagged, or placed in rigid containers.

Sterilization modalities are taught in comparison:

– Steam sterilization: Common for heat-tolerant items; cycles balance temperature, pressure, moisture, and exposure time.

– Low-temperature processes: Useful for heat- and moisture-sensitive devices; they require validated lumen lengths and load configurations.

– Liquid chemical sterilants and high-level disinfectants: Applied for specific device categories and reprocessing needs, with careful attention to contact time and material compatibility.

Monitoring and documentation are non-negotiable competencies. Trainees learn to interpret physical printouts or digital records, place chemical indicators correctly, and use biological indicators at defined intervals to verify process lethality. Quality systems round out the curriculum: lot control, load release criteria, recall procedures, and root cause analysis. Learners practice reading device instructions, comparing them with facility policies, and resolving conflicts by escalating appropriately. The overarching goal is consistent, reproducible outcomes that approach a widely accepted sterility assurance target for terminally sterilized items, supported by traceable records that stand up to internal reviews and external audits alike.

Hands-On Skills, Equipment, and Daily Workflow

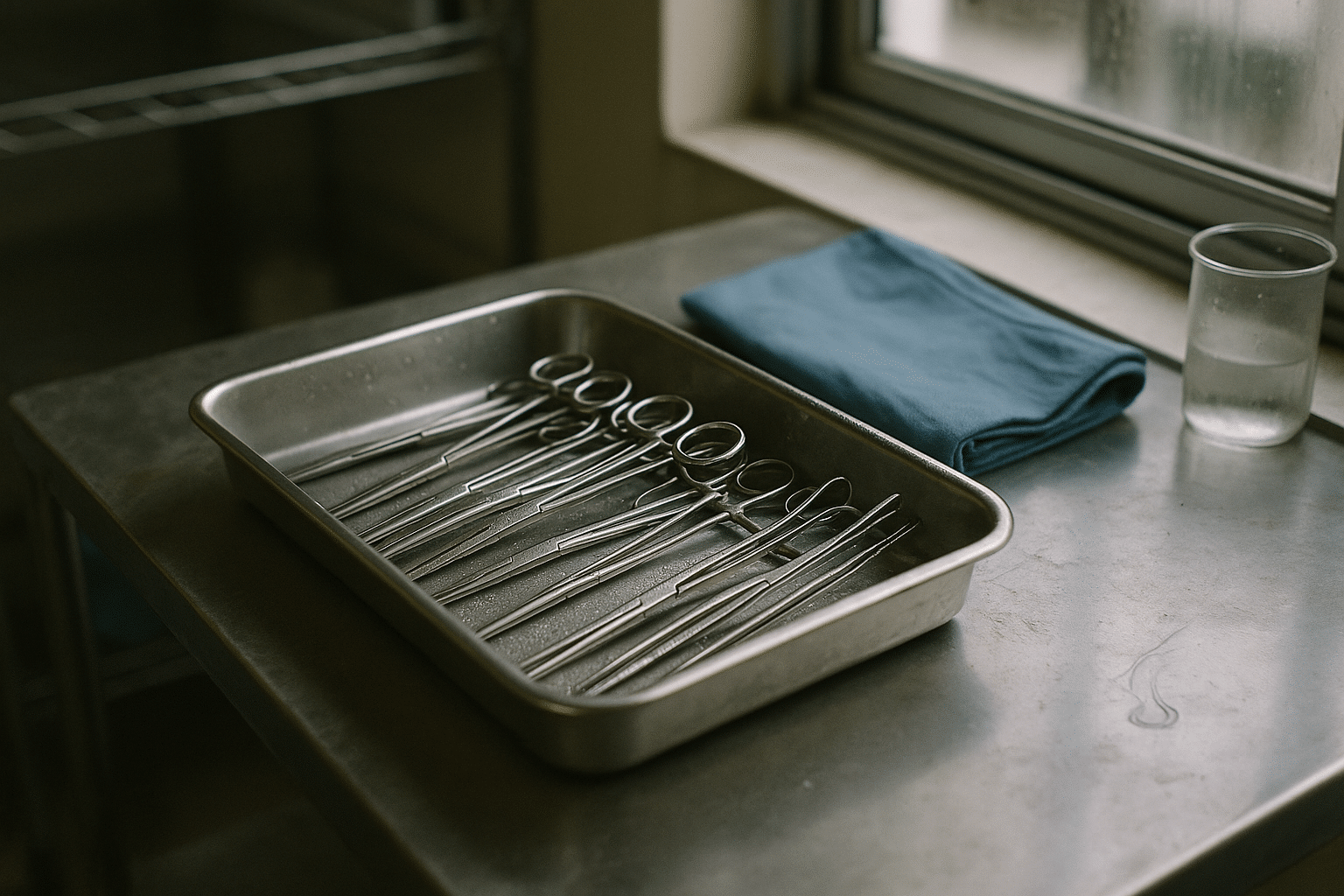

Beyond textbooks, mastery develops at the sink, the assembly table, and the sterilizer loading area. A well-designed department flows from dirty to clean to sterile, with physical separation and clear signage. Trainees start by suiting up in appropriate protective equipment, verifying transport container integrity, and sorting items by device type and cleaning method. At the sink, technique matters: brush selection that fits lumens, stroke counts that reach all surfaces, and rinse practices that reduce residue without splashing contaminants. Mechanical equipment—ultrasonic units and washer-disinfectors—expedite cleaning, but proper loading, instrument spacing, and cycle selection are indispensable.

On the assembly side, novices learn the language of instruments: joint types, serrations, ratchets, and insulation on electrosurgical components. Under magnification, they inspect for cracks, worn teeth, misaligned jaws, or insulation defects. Count sheets guide set composition, yet critical thinking catches mismatches or wear that a list cannot. Packaging becomes a craft: selecting wraps or pouches that fit, adding protective tip guards, and arranging items to support sterilant contact and aseptic presentation. Rigid containers demand gasket and filter checks; indicator placement must be visible and interpretable.

Sterilizer loading and release decisions follow a disciplined pattern:

– Verify load configuration matches cycle parameters and device instructions.

– Avoid overloading; allow for adequate air removal and sterilant penetration.

– Place indicators per policy and separate implants or complex devices as required.

– After the cycle, review physical records and indicators before releasing the load.

Daily workflow also includes storage and distribution. Sterile items require controlled temperature and humidity, with shelving that avoids crush or moisture risk. Technicians rotate stock, protect packaging integrity, and respond to case cart requests with a service mindset. When nonconformances arise—wet packs, compromised wraps, incomplete documentation—the team pauses, investigates, and corrects. Success in this environment looks like predictable outcomes: trays arrive complete and sterile, logs are accurate, and the operating room starts on time. With repetition, speed follows accuracy, and confidence grows without cutting corners.

Exam Prep, First Job, and Long-Term Growth

Certification validates knowledge and signals readiness to employers. While exam names vary by region, content domains commonly include decontamination, instrumentation, packaging, sterilization, microbiology, and quality systems. A practical study plan spans eight to twelve weeks for new learners, or four to six weeks for those with experience. Build momentum by scheduling daily, focused sessions and rotating topics to reinforce memory. Practice questions expose weak spots; scenario-based drills sharpen judgment about load release, recall decisions, or conflicting device instructions and facility policies.

A balanced preparation approach might include:

– A weekly cycle: one science-heavy topic, one process topic, and one quality topic.

– Daily quick reviews of terminology, symbols, and instrumentation profiles.

– Weekly timed quizzes to simulate test pressure and pacing.

– A personal error log to track misunderstandings and write brief corrections.

– A final-week sweep of high-yield charts such as indicator types and process parameters.

Landing the first job benefits from clarity and evidence. Tailor your resume to highlight clinical hours, documented competencies, and any process improvement contributions from training. In interviews, be ready to discuss a time you identified a nonconformance, how you escalated it, and the outcome. Employers value individuals who are coachable, communicate well, and protect patient safety even when production pressure rises. Once hired, keep building: pursue cross-training in endoscopy reprocessing, advanced instrument repair assessment, or inventory data systems. With consistent performance, roles can broaden into lead technician, instrument specialist, educator, or supervisor, often with wage increases tied to skill tiers or additional credentials.

Continuous learning anchors long-term growth. Many regions expect ongoing education credits to maintain credentials, and wise technicians exceed the minimum. Track department metrics—wet pack rates, repair rates, turnaround times—and participate in improvement projects. Seek mentorship, read device instructions regularly, and volunteer for new service lines to expand your instrument vocabulary. Over time, you become the colleague others turn to when a tricky device arrives or a load alarm sounds. That quiet reliability is a career asset, and it starts with thorough training, thoughtful practice, and a commitment to doing the small things right every single shift.